Generative AI in journalism

Our take on ChatGPT et al

Asking the right question...

Malmö, January 2023

“What do you think of ChatGPT in the context of journalism? Saviour or enemy? Will AI make or break the news industry?” This is certainly the question du jour in our industry.

We suggest it’s the wrong question. After seven years of providing automated articles to newsrooms (using a different type of AI), at United Robots, we’ve heard it all before. The fears of robots stealing jobs, of factually incorrect, untrustworthy content written in robotic language…

It turns out that – surprise, surprise – reality is never as black-and-white as fears suggest.

And in the case of this newer, generative AI (used in e g ChatGPT) – from where we stand – the scope is at once immense and limited. So, rather than focus on “saviour or enemy”, let’s take a step back and ask the question: “What can generative AI do for journalism, and what can’t it do?”

And – most importantly – what role should people play in this process?

Publishers are in the driver's seat

ChatGPT is just a tool – albeit a brand new, powerful tool with huge scope, but a tool nonetheless. It does not change the guiding principles of journalism – a fundamentally human activity.

Of course this type of AI can be used for nefarious ends, but so could the printing press. We are in the business of journalism and we should work out how the new tools can help us do that even better – as well as identify what risks may be involved.

In mid January (2023), Futurism broke a story that perfectly illustrates the latter. Publisher CNET is using AI to write short financial articles, but has not been open about it. Some of the aspects of this story shine a bright light on the choices publishers have, irrespective of what type of AI they use:

Transparency. We always recommend that AI written articles have a byline which makes it unequivocally clear that it was written by a robot, not a reporter. Transparency is critical internally as well as externally, and key for trust. In the case of the CNET story, the Verge reports that there seems to be a lack of transparency around the actual purpose of the content too. According to the Verge, the business model of CNETs relatively new owners Red Ventures, is about creating content designed to get high rankings in search, and then monetise the traffic. Their business model is not publishing journalism for people.

Accuracy. It goes without saying that any content published within a journalistic platform needs to be correct and reliable – whether it’s a groundbreaking investigative piece by a seasoned journalist or a small text about a local football match or financial news. AI tools always need to be controlled by journalists. And if you’re going to auto publish AI generated texts, you cannot use generative AI tools like GPT-3 / ChatGPT – see explanation in fact box (right).

Everyone is talking about AI – but what are we talking about?

As tends to happen with buzzwords, any original definition of AI is gradually being replaced by whatever meaning people perceive it to have. Here, we're going to limit ourselves to clearing up some confusion around the types of AI used for text generation. There are two basic models:

• Data-to-text models, (built on rules based AI, see below) which create text based on sets of structured data like sports results or financial data. This type of tech is what many of the first text robots were built on, it’s the model for self-service tools like Wordsmith and Arria, and the data-to-text model is what we use. The key feature here is that it’s data based. In other words, the model includes facts from the data, and no other “facts” in the text. Factual correctness is basically guaranteed.

• Text-to-text models, (built on generative AI, see below) a k a Large Language Models, which use deep learning to create text based on existing text – in the case of GPT-3 on 175 billion parameters of human language drawn from the internet. While these models can create good language, they work from prompts, not from data. Factual correctness cannot be assumed. Because while an LLM is able to refer to all accessible information, and include it – more or less randomly – in a text, it is not able to do fact checking.

And what about ChatGPT, specifically?

The free ChatGPT party may not last. Last time we checked, the beta access provided by OpenAI was running at capacity, and it’s unlikely to stay free indefinitely. So – any media company wanting to leverage these types of language models for real editorial/business implementations should take API access and costs into account.

This is not the first, nor the only one. ChatGPT is a chatbot (i e it’s optimised for conversations) built on OpenAIs large language model GPT-3.5, a model that’s been available for some years. Its earlier version GPT-3 was commissioned by The Guardian back in the autumn of 2020 to generate a robot written op-ed – which got a lot of attention at the time. (The Guardian also published an interesting article about the whole process, which involved a fair bit of cutting and editing before the op-ed could be published.) Also, important to point out that OpenAI in San Francisco is just one of many providers of generative AI tools.

This article is focused on generative AI specifically for language generation. Generative AI can be built into tools for many other purposes too, including generating images (such as Open AI’s DALL-E), code, video, reading recommendations and so on.

Trust. The issue of trust really encompasses both of the above. Trust is the currency of journalism. Any deployment of new tech tools must in no way leave room for people to question the integrity of a publication. Having said that, we’ve found that readers are generally happy to embrace robot written content – as long as the information is valuable to them, and clearly labelled.

If a publisher asked “What does generative AI mean for our business?”, we’d like to ask back: “What do you want it to mean? The AI is not in control, you are.”

We would advise publishers to keep focussing on delivering solid, valuable journalism and use generative AI tools where they are helpful in this mission. Charlie Beckett, director of the JournalisAI project at LSE expressed it perfectly in a podcast recently, saying that these tools cannot ask critical questions or work out the next step in investigating a story, but that they can be a support to journalists in doing this work. “But I think it’s even more interesting how it puts a kind of demand on those journalists, saying ok – you’ve got to be better than the machine – you can’t just do routine, formulaic journalism anymore, because the software can do that.”

We’re only at the beginning of exploring how generative AI can support the business of journalism. Trying out ChatGPT is easy – working large language models into robust and useful processes within a publishing business will be considerably harder. It will be crucial to keep a razor sharp focus on the use you’re trying to extract from the tech and not get sidetracked by its inherent capabilities.

At United Robots, we’re testing a number of possible uses for large language models, including prompting them to turn text into structured data (our “raw material”), also attempted elsewhere. It’s early days, there are lots of opportunities, and the measurable use and value we can derive from this tech is what will ultimately determine how we deploy it.

Good journalism is about people – those who produce it and those who consume it. It’s about the unique work and voices of great reporters, something that can’t be replaced by ChatGPT. It’s about meeting the needs and expectations of readers, in a way that differentiates yours from other publications. Large language models are not able to work out what your unique product should be.

AI can help improve our work processes, but it cannot produce journalism.

Let’s not have an identity crisis.

Rules based AI vs generative AI

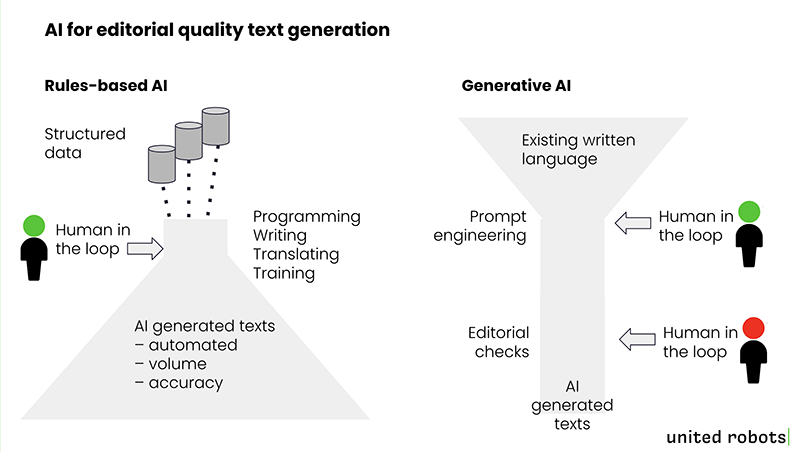

> Rules based AI. In terms of generating automated fact based text, you can only really gain efficiencies by using rules based AI (at least at this point in time). With the United Robots platform (left in illustration) – and our model where we sell content rather than deploy tech – the all-important human(s) in the loop are involved before the text generation. The raw material is structured data from reliable sources.

• Our team programmes the robot

• Word, clause and sentence alternatives are also written by humans. As well as translated if we’re building for a new market.

• When a new publisher is onboarded, this is also where they are involved. Our language team helps editors train the robot to the editorial guidelines and needs of their particular newsroom.

Once all that is done, the humans’ work is done and the robot automatically writes and distributes texts to whatever end points the publisher needs.

With the human in the loop before text generation you can create volumes of texts with guaranteed accuracy – as long as the data is correct. The content is scheduled, and publication predictable and can be automatic.

> Generative AI. By comparison, to the right in the illustration is what generative AI looks like for editorial quality text generation. The human in the loop needs to be involved in two sets of processes.

• Someone needs to create the prompts to drive the text generation, as well as optimise prompts to refine the outcome.

• Even after that, in order to guarantee accuracy and editorial quality, you also need to have someone check the facts, sources, conclusion etc in any AI generated text.

At this point it's hard see efficiency gains with generative AI for automated text generation.